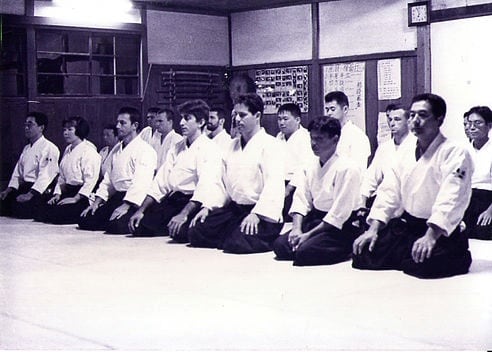

It was early 1998, and I had just finished an eight-year phase of life, living in Japan. I had been studying Aikido full time with my teacher Morihiro Saito Sensei, at the famous Iwama dojo. Even though I had achieved a sense satisfaction in what I had accomplished during this time, there was also a subtle itch of wanting something more, something I wasn’t finding in my Aikido life in Japan.

When I left Japan at the end of 1997, I was told by Saito Sensei to return to the U.S., open a dojo and start teaching Aikido. In many ways, I was ready for this commitment. I had been training intensively in Iwama for eight years, was in my mid-thirties, had gotten my 4th dan, had become fluent in Japanese, and I was even translating for Sensei. I had learned much about Japanese culture from the inside, and I had been teaching Aikido two times a week in Japan for three years. I felt confidence in who I had become, and this confidence served as a solid foundation upon which I had built my identity. However, beneath all my confidence I could not deny that there was something missing. I had a spiritual calling that could no longer be ignored, and it was this calling that became the guide for my next move in life.

The famous Iwama Dojo, in Japan, helmed by Morihiro Saito Sensei.

A Spiritual Calling That Could Not Be Ignored

It seemed that all of my growth and development, as valuable and beautiful as it was, was only touching one dimension of my existence, spreading out nicely on the surface, but not penetrating to the core of my being. So I decided to travel for a year to seek out spiritual teachers and undertake formal spiritual practices.

During the last three years in Japan I had taken on regular practices which included “A Course in Miracles,” and daily 30 min. meditations. These were all informal self-practices done without a teacher, or guide. I was largely inspired by the many spiritual books that I was reading at the time. Two of the books that had a particular impact on me were by American Vipassana teachers; Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfeld. Both of them had practiced in Burma and from all the teachers they spoke about in their books, one name kept catching my attention. He was the Burmese meditation master Sayadaw U Pandita. In fact, when I first read his name, U Pandita, it had the karmic effect of working its way deep into my consciousness. I connected with the method of practice that they taught and with that inspiration I decided to make my way to Burma, to find U Pandita and to practice Vipassana meditation.

Even though I was quite sure I wanted to commit to a formal spiritual practice I was still quite attached to my own ideas (and baggage) about Aikido being a ‘spiritual path.’ After all, O Sensei’s life was a testament to the classic spiritual journey. So when I began my spiritual journey, I managed to pack the ‘Spiritual Aikido’ ideal tightly into my traveler’s backpack. I did this by conveniently planning that my visit to Burma would coincide with an Aikido seminar that a Japanese teacher friend of mine would be leading. My plan was to do a 10-day retreat, then the one-week Aikido seminar, followed by another 10-day retreat. Spiritual practice and Aikido practice. I had arranged things nicely so I could have my cake and eat it too. Perfect! Or so I thought…

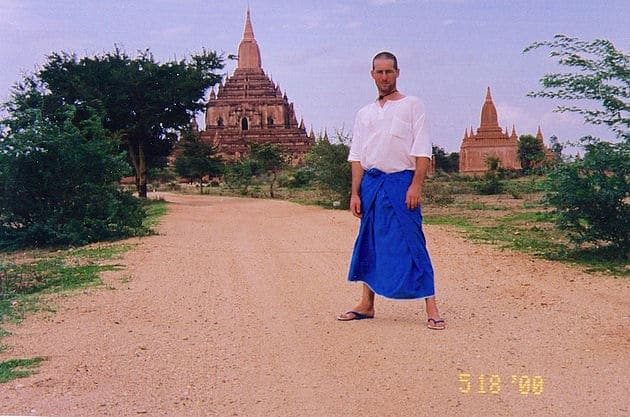

After a two-month teaching stint in New Zealand, and some rest and relaxation in Thailand, I decided it was time to get on track with the main purpose of my trip, meditation in Burma. I caught a plane to Rangoon and made a bee-line to the Panditarama Meditation Center, and to U Pandita himself.

I Was Sure U Pandita Would Be Impressed…

Upon arriving at the center, I was told that Sayadaw U Pandita was away for the day and wouldn’t get back until the evening and that I should check into a hotel and come back the next day. I explained that I had come a long way and that I was there to meditate, so they allowed me to sit and wait in the office until U Pandita got back. He eventually did return after seven hours, and when he was told I had been waiting to see him he glanced over his shoulder at me (I had a sense that he was sizing me up), and he agreed, with a slight sense of irritation, to interview me. I was quite confident I could overcome what seemed to be U Pandita’s first impression of me. Having learned much about discipline and proper etiquette while living in Japan, I did my best to showcase these qualities to him. In fact, I was sure U Pandita would be impressed. After all, who wouldn’t be?

When I entered U Pandita’s quarters I was immediately struck by his strong presence. It completely dominated the room, indeed the whole meditation center. I also had an uneasy sense that he saw a part of me that I wasn’t seeing. So whilst there was an immediate feeling of trust, I also felt exposed and unsettled in a very subtle way. Nonetheless, I did my best to make a favorable impression while answering through the translator several questions from U Pandita.

He asked about my background in meditation (self-practice for the past two years), my purpose for coming to meditation (spiritual liberation), and why Panditarama (I wanted to train in the Mahasi tradition). U Pandita also asked me about my plans in Burma and I made a feeble attempt to explain that I planned to do a 10-day retreat, then leave to attend the Aikido seminar for a week, after which I’d come back for another ten days of meditation practice. He briefly asked what Aikido was, but it seemed that this got lost in translation and I didn’t think he got it. Nonetheless, it didn’t feel like the right time for further explanation, but I was sure that if the opportunity ever arose again to have a conversation about Aikido and spirituality, then all would be well. For now, all that mattered was that U Pandita agreed to allow me to stay and practice on probation. I was in!

A Teacher I Could Place My Absolute Trust In

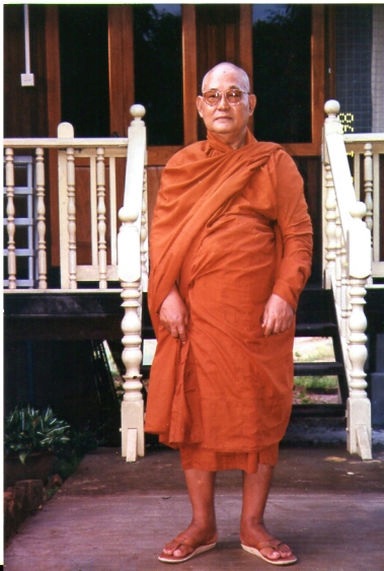

During the next ten days of practice, I received daily interviews and Dharma talks with U Pandita, and I soon understood why he had such a renowned reputation. Here was the master I had been seeking my whole life. Having been a monk for over 70 years and a meditation teacher for 50, his wisdom and skillful guidance was like nothing I had ever encountered before. But even more impressive was his presence as a spiritual warrior. I had never experienced in another person, such complete fearlessness, confidence, uncompromising determination and skill in teaching. I didn’t really have the capacity to understand it fully, but U Pandita had a strength that was unshakable. It would take me many, many months of practicing on retreat, indeed a few years, before I began to understand the source of that unshakable strength. Here was a man deeply grounded in the absolute truth, the ‘Dhamma’ of ultimate reality, and it made everything in me that was relative, feel extremely limited. I knew that here, in this teacher, I could place my absolute trust.

The irony did not escape me. I had spent much of my life in the martial arts seeking for the warrior ideal. Now here I was meeting that ideal in the form of a simple monk. A man who was deftly wielding the sword of truth and the shield of concentration together with a heart of loving kindness and compassion.

Master Sayadaw U Pandita. “Complete fearlessness, confidence, uncompromising determination and skill in teaching.”

U Pandita taught that 100% of all the suffering in the world had its source in the mind. The world, he said, is full of external enemies, but it is the internal enemies that are far more dangerous. These enemies come in the form of mental impurities, and the purification of the mind is where all true battles must be fought. In this, he was uncompromising and relentless. He would be brutally direct when necessary. The Buddha, he taught, was like a doctor, who knew exactly which medicine was needed to cure, or awaken the patient. All the medicines he gave fell into two types; sweet medicine (loving kindness, compassion, and support), and bitter medicine (truth, discipline, and challenge). U Pandita unapologetically proclaimed that he gave the bitter medicine. Sooner or later all yogis got to experience a full dose of his tough love, and if that didn’t scare them off, then they also had the experience of its cure. I had finally found the teacher I wanted to be practicing with, the practice I wanted to be doing, and the place I wanted to be practicing. This was it! I just had to go and attend an Aikido seminar, and then I’d be right back.

So when the first ten days were finished, I packed my backpack and headed off the seminar. On my way out I stopped in the center’s office to let them know that I would be back in one week. The office staff member stepped out to pass on my news and upon returning I was told, much to my surprise, that in fact, I could not come back. Of course, there must have been some misunderstanding. With full confidence that I could clear this up, I insisted on meeting with U Pandita to explain my situation and get permission to return.

On Some Sort Of Cosmic-Karmic Threshold

I was asked once again to wait and sat in U Pandita’s interview room meditating, and in my mind working out the story I would tell him so that I could come back. After about three hours I was finally taken to see U Pandita, as he was overseeing the unloading of a new Buddha statue to the monastery. In another moment of irony, I thought to myself “the Buddha has just arrived, and I am leaving.” So there we all were, on some cosmic-karmic threshold. The incoming Buddha, the ever present U Pandita, and the outgoing me.

U Pandita gave me half of his attention and asked what I wanted. I explained my situation with the Aikido seminar and that I would be back in a week for more practice. He told me that I had done well, but I couldn’t come back until the next time I was in Burma. I agreed that I hadn’t planned things well and apologized for this but explained that I had to go to the Aikido event. I apologized for this and said I was sorry that I was leaving in the middle of my stay, and told him that I really wanted to come back and continue the practice in a week. Yet, somehow, U Pandita didn’t seem moved by my display of sincerity.

I was beginning to feel that my reasons for leaving were perhaps a little weak, but I was convinced that this was a legitimate excuse. If I could just convey that to U Pandita, surely he would understand. After all, we were talking about Aikido, a spiritual martial art, and it was just a matter of convincing him. So I told him I wasn’t planning another trip to Burma and I wanted to meditate more on this trip. He responded with a glance and deafening silence. My steadfast confidence began to waver, and I suddenly had a sense that I was standing on thin ice. I further explained that I was going to be the translator for the whole event and that I was a key person for the seminar. More silence from U Pandita and an uncomfortable feeling that I was sliding further out onto the thin ice. I continued in a somewhat desperate manner to explain that the Aikido seminar was planned months ago and that I had already committed to going. Then U Pandita asked me again “What is Aikido?” (This wasn’t the Aikido conversation I had envisioned). Somehow it was translated as a ‘martial art.’ As I stood there, hat in hand, there was something profoundly unsettling about the way U Pandita was looking at me. He was quite generously giving me all the rope I wanted. I was methodically wrapping it around my neck. The intensity of U Pandita’s silence was like a mirror, and the reflection was undeniable and unsettling. I was slowly beginning to understand that I was choosing to leave a 2,500-year-old practice of spiritual liberation to go practice a ‘martial art’…for my ego. The ice began to crack.

When You Have Spiritual Protection…

Then, turning on me with full presence, U Pandita looked me in the eye and in English said, “When you have spiritual protection, you don’t need martial protection.” It is hard to describe the effect these words had on me in that moment. Up until then, I had invested many years in the belief that Aikido was a ‘spiritual’ martial art. O Sensei was proof of this. I loved the martial training and had dedicated my life to its perfection. I assumed that it would naturally lead me to the spiritual if I ‘just kept training.’ An unquestioned promise of a future enlightenment if I just kept doing my technical Aikido training. But I was attached to the martial and I wasn’t willing to let it go to move into the spiritual aspect that was in fact, my heart’s deepest desire. Indeed, this was the very reason why I had come to Burma. But in this unbearable moment of truth, the uncomfortable fact was that I wanted to have my cake and eat it too. I was clinging to years of investment in Aikido as I understood it at that time, and it was the very thing that was holding me back.

My future and past were all hanging in the balance in that very moment with an unbearable intensity. Then with U Pandita’s words, “When you have spiritual protection, you don’t need martial protection,” the ice suddenly gave way, and I fell into the abyss. My knees buckled and the ground seemed to become unstable. In a moment, with one perfectly placed Zen whack, I was stripped of my identity. I was totally disoriented and was left with nothing to hold on to. My self-deception was exposed for the sham that it was, and what was revealed was what had always been there at the bottom of it all. My total insecurity. I was at a complete loss as to what to do, so I grasped for the only thing that was left. I gave in and surrendered. In that moment I told U Pandita I wouldn’t go to the seminar. With tears in my eyes, I begged him to let me stay and practice. He then did something I never even conceived as being possible. He unceremoniously told me “No” and sent me away like a schoolboy.

I couldn’t believe this was happening. I had been dismissed. I was thrown out. Completely disoriented I hefted my backpack, (which was suddenly very heavy) and stumbled out of the monastery in a daze. I found my way to a taxi and about half an hour later I was sitting in a Japanese restaurant in downtown Rangoon drinking a beer with my Japanese friend. It was totally surreal and utterly meaningless. Still in a daze from this ego destroying encounter with U Pandita, I did my best to put on a good front and engage my Japanese friend in Aikido talk. He went on and on about how great the coming seven-day Aikido seminar was going to be. Of course, it wasn’t.

When the time came to leave Burma, I stopped by the monastery on the way to the airport to ask U Pandita if I could return to practice on my next visit to Burma. U Pandita gave his permission and six months later I was sitting my first three-month intensive Vipassana retreat with him. My ‘year of travel’ turned into eight, and I spent each winter returning to Burma for meditation retreats.

You may be wondering why I am sharing this story as one of my significant, if not my most significant Aikido experience. This was the point that all of the false ideas that I had built about Aikido were unpleasantly exposed. I was sure of Aikido’s spiritual depth, but I was looking for it in the wrong place. The source of spirituality is not to be found in the physical, nor does it exist in the martial. It can be expressed in these realms, but its source is beyond. My attachment to Aikido was the very thing that prevented me from realizing this. And this encounter with U Pandita was the beginning of correcting that mistaken view.

It was a hard lesson, but it changed my path in Aikido. Indeed it changed the direction of my whole life. Because it was only after I managed to let go of what I had made important in Aikido, that Aikido’s deeper value began to emerge.

And it happened with the words of a simple monk.

Please note: I reserve the right to delete comments that are offensive or off-topic.